90 Years (and 54 feet) of "Trouble" at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences

Thursday, April 05, 2018, 2pm by visitRaleigh

Ninety years ago, "Trouble" appeared on the beach in N.C.

On Wed., April 5, 1928, a resident of Wrightsville Beach stepped outside of his beach-front home to get the morning paper. What he found instead was a massive sperm whale—54 feet long and weighing 100,000 pounds—that had washed ashore in his front yard. The whale would later come to be known as Trouble—a valuable specimen and an icon for many years now at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in downtown Raleigh. What follows is the short story of the monumental effort it took to bring Trouble back to Raleigh.

A note: the information here, as well as the photos from 1928 below, comes from a 66-page digital resource document in the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences' Brimley Memorial Library titled "Trouble."

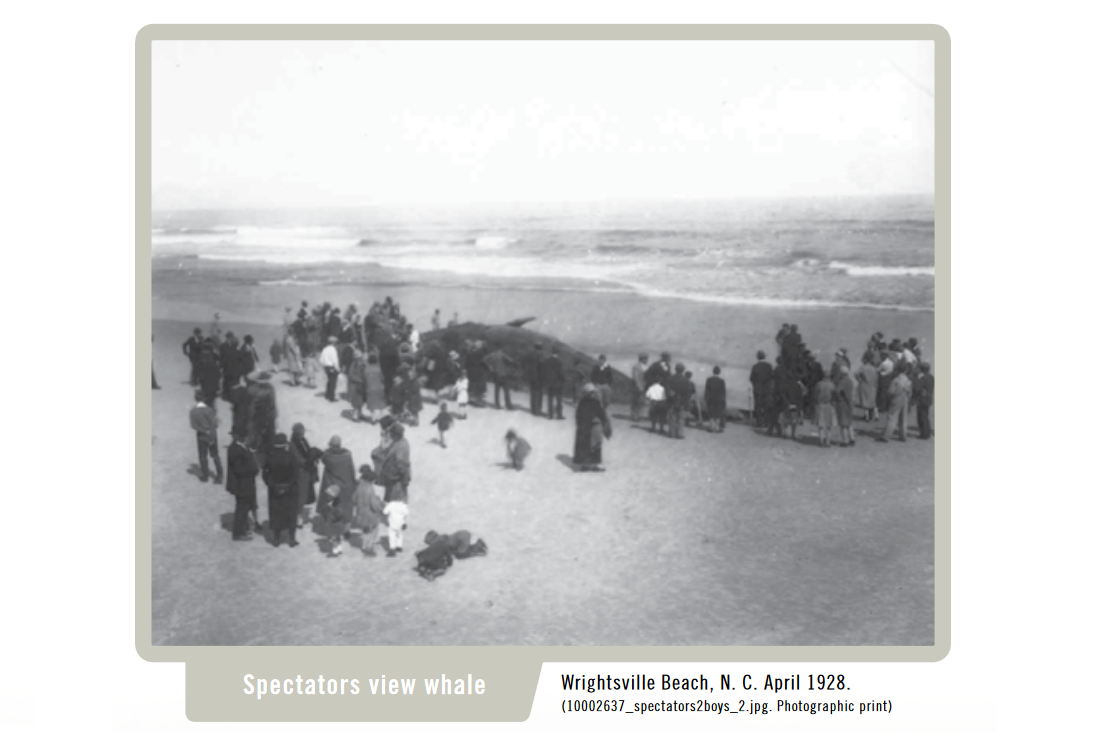

The 55-ton whale had already been dead for four days when it washed ashore, presenting the first of many problems to follow—health officials demanded the whale be removed from the area immediately. Despite the smell (unpleasant to say the least) the mayor of Wrightsville Beach knew of a group that might be interested and able to handle this conundrum—the State Museum in Raleigh. The whale certainly had value—at the time, only five skeletons of any whale specimen were hanging in American museums. Museum director H.H. Brimley was absolutely interested. He and his assistant, Harry Davis, set off for Wrightsville the following morning to evaluate the scene.

Brimley and Davis weren't the only ones to show up (not by a long shot!). It's believed that 50,000 visitors from a half-dozen states traveled to see the carcass.

Davis and Brimley estimated a seven-day timeframe to remove and dispose of the flesh from the whale and bury the bones (to allow a natural cleansing process to take place). Deemed far too long and unacceptable, town officials immediately ordered a local marine towing company to drag the carcass 20 miles out to sea.

Determined to come away with something of value for the museum, Brimley asked Davis to obtain the lower jaw bone of the whale before it was taken away. Several hours of laborious sawing later, the 600-pound portion of the jaw had been removed. While transportation for the jaw was being arranged, local police would watch over it for a day or two. Mysteriously, the jaw bone disappeared and was never to be seen again. Letters sent to and from Brimley at the time show that foul play was suspected—made from ivory, the teeth of the whale (50 to 60 of them) were worth a considerable amount of money.

Next, a stroke of good fortune—a failed attempt at moving the whale by the towing company, then a storm that caused a several-day delay—allowed Brimley to arrange to have the carcass moved not 20 miles out to sea, but 20 miles north, to a sparsely-populated area of Topsail Island. If all went as planned, the museum would get to save the entire skeleton after all.

But it certainly wasn't going to be easy.

On Fri. the 13th, eight days after Trouble washed ashore, the towing company succeeded in moving the whale away from Wrightsville Beach—unfortunately, they missed the drop off point at Topsail by one mile. A five-hour struggle finally got the whale back on shore again, where a few days later Davis planned to start the "cutting-in" process.

When Davis arrived at Topsail, he found the carcass a half-mile out into the inlet, now resting on a sand bar. The wires holding the whale in place on the beach had been deliberately cut—sabotage again! That was just the beginning of issues in the Topsail area. During the two weeks that Davis worked on the carcass (waist deep in the sea at this point), local residents complained to the health department, cried that the whale created a poor fishing environment (in a letter to a congressman, one fisherman sought damages of $15 to $20) and taunted Davis and Brimley about knowing the whereabouts of the lower jaw. "It's Hell!," Davis wrote in a letter to Brimley on his progress.

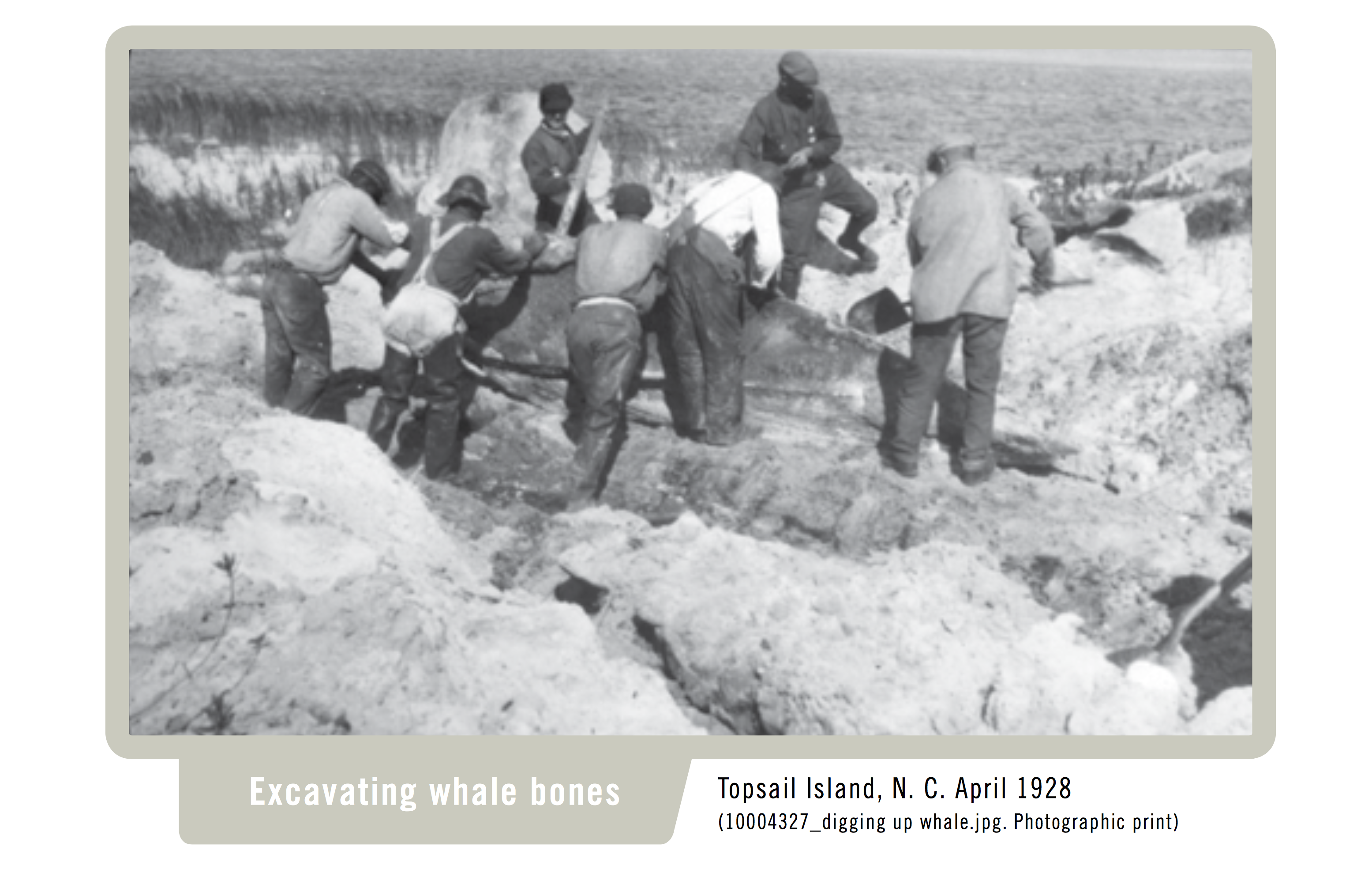

On April 27, after weeks of hard work and nagging problems, Davis' work was complete. The bones, buried in the sand of Topsail Island, would remain untouched for the next six months.

Half a year later, Davis returned to dig up the more than 100 bones and take them back to Raleigh. Loaded and ready to go, the first truck became stuck in the sand, necessitating a trip to Wilmington to find a chain that could pull the truck out. That chain? It snapped in half. A second trip to Wilmington and a second chain later and eventually the bones were headed towards Raleigh where they were buried in fresh sand at the North Carolina State Fairgrounds.

In Dec. of 1929—a year and nine months after Trouble first appeared—the bones were clean, dry and ready to be put together. The six-week project, with half that time devoted to just the skull, was led by Brimley.

Having never recovered the lower jaw, a new one—from a nearly identically-sized whale—was purchased from a private curator for $40. It came with just two teeth. Brimley fashioned 42 more fake teeth with dental plaster mixed with yellow ochre to complete the skeleton.

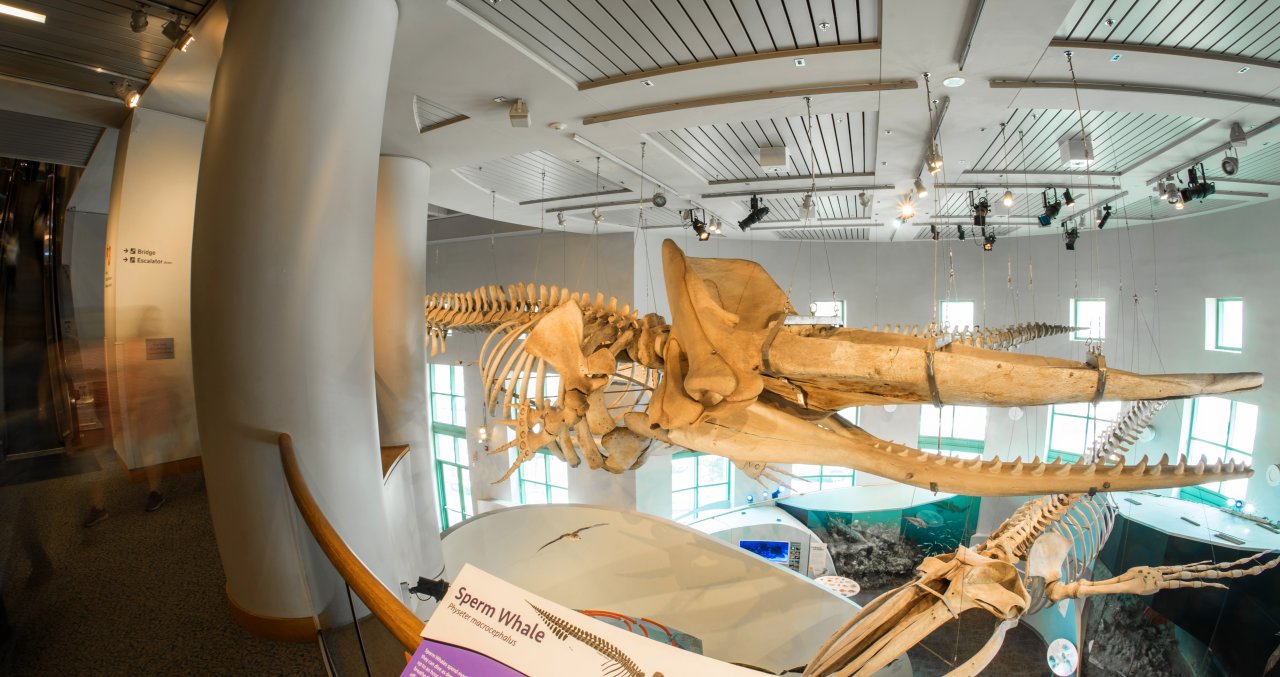

Finally completed, the skeleton went on display in Feb. of 1930, suspended from the trusses of the second floor ceiling in the museum just as it is today (though the museum has moved locations multiple times, once requiring the skull to be taken apart because there were no doors big enough for it to fit through).

Upon being revealed to the public in 1930, Brimley—who passed away in 1946 after having spent nearly 60 years in Raleigh dedicated to the museum—called the skeleton "the most outstanding and valuable individual specimen the museum has ever secured."

Brimley named the whale Wrightsville—the name didn't stick. Friends and colleagues had tongue-in-cheek been referring to the mammal as Trouble, and that was that.

Today, Trouble hangs majestically in the Coastal North Carolina Hall of the museum, where visitors can gaze up in awe from the first floor or get a closer view by moving to the second floor overlook. Joined by several friends—a massive blue whale, a rare True's beaked whale and an endangered right whale—this section of the museum boasts one of the most impressive whale collections in the country.

Created in 1879 (nearly 140 years ago!) the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences is an always free-admission gem in downtown Raleigh. Housed in its current location since 2000, the museum opened a new wing—the Nature Research Center—in 2012 to act as a mixture of visitor destination, research hub and hands-on student laboratory (another whale, Stumpy, stretches 50 feet across the first floor of the new building).

The museum attracts nearly a million visitors per year—946,486 visitors walked through the doors in 2017, making it the fourth consecutive year that the museum was the most popular tourist attraction in the state.

More Articles You Might Like

-

30 Can't-Miss Things to Do in...

Raleigh, N.C., is a booming metropolis that offers a big city feel with Southern charm. It's a smart,...

-

Incredible Chainsaw Art at William...

Note: This article was first published in November 2017. This incredible piece of art has been kept in...

-

20 of the Best Brunch Spots in...

Weekends are meant to be brunched on! Time spent with family and friends over stacks of blueberry pancakes or...

Author: visitRaleigh

The Greater Raleigh Convention and Visitors Bureau (CVB) is the official and accredited destination marketing organization (DMO) for all of Wake County.